Forgotten at Home, Famous Abroad (III)

Jeong Chu’s Songs of Goryeo

Forgotten at Home, Famous Abroad (III)

Interview by Jeong Jiyeon

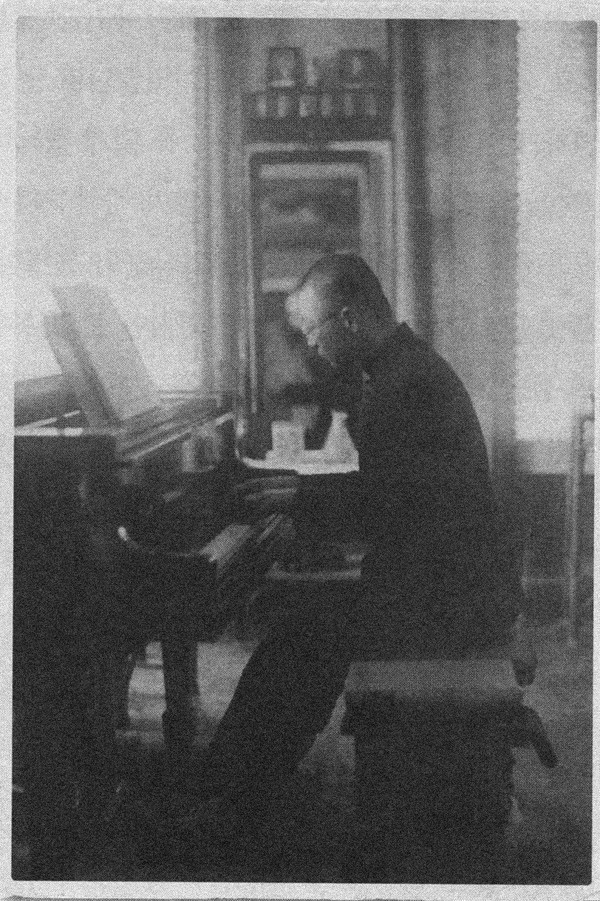

This article aims to shed a new light on the life of Gwangju’s forgotten musician, Jeong Chu, a Gwangju-born emigrant caught up in Korea’s turbulent modern-day history. His life was reconstructed through an interview with Mr. Jeong Heon-ki, a culture and arts planner. This concluding article continues from “The Black-Haired Tchaikovsky” in the November issue of the Gwangju News.

During his studies at the Moscow Conservatory in Russia (then the Soviet Union), a warrant to arrest Jeong Chu was issued by the North Korean authorities with the accusation that he was promoting a movement against the idolization of Kim Il-sung. In response to this, Jeong Chu wrote a letter to Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, to seek political asylum. Consequently, instead of being forced to return to North Korea, he was deported to Almaty, Kazakhstan. It was not until 17 years after being deported to the Soviet Union, in 1975, that Jeong Chu was able to receive Kazakhstani citizenship.

Jeong Jiyeon (JJ): It is said that Jeong Chu was deported to Almaty, Kazakhstan, for demonstrating against Kim Il-Sung's idolization in Russia. We are curious to hear what his life was like in Kazakhstan and what he did while there.

Jeong Heon-ki: In 1958, after arriving in Kazakhstan, he came across the “Goryeo people” (Koreans in the Soviet Union who were exiled to Central Asia by Stalin). However, as you probably are very well aware, Stalin committed many atrocities against the Goryeo people in Central Asia, which deeply shook Jeong Chu. It left such a big impact on him that there is even a symphony he created, inspired by the deportation of the Goryeo people to Central Asia called” September 11, 1937, Stalin.”

Another great achievement of his during this time was that he recorded the musical oral heritage of the Goryeo people. He took a state-of-the art portable recorder of the time, which had just been released, and got on board the Trans-Siberian Railway. He recorded, as well as wrote down, musical scores of the songs he heard from the Goryeo people he met along the way. In this way, he collected over 1,000 traditional songs. I truly believe that the reason why he was able to immerse himself in this way in studying folk music was because, as a musician, but also an immigrant himself, he could, like no other, feel the sorrow and grief that the Goryeo people experienced due to alienation.

Interviewer’s Note: The early days of Jeong Chu’s exile in Kazakhstan gave birth to all of his most representative orchestral music pieces. Following that, starting at the end of the 1970s all the way until the year 1990, he focused mainly on his research as a folk music scholar, as well as on educational activities as a university professor. What is more, about 60 of his works were featured in Kazakh music textbooks, and in 1988, he was awarded the title of "Honored Cultural Worker of Kazakhstan" by the Kazakh government.

JJ: We would like to hear your opinion, as a descendant of Jeong Chu, about what kind of musician you would like him to be remembered as.

Jeong Heon-ki: It seems to me that people tend to, more or less, take an eventful approach to Jeong Chu’s life. When researching about his life and achievements, one cannot help but think about their sociological, economical, and political effect. However, reflecting on the circumstances of the era, I hope that more light is shed on what kind of life he lived as a Korean born during the Japanese colonial era, as a post-war (both of World War II and the Korean War) musician when the ideologies of the day were sharply opposed to each other.

Also, apart from Jeong Chu, there are many more amazing people from Gwangju in modern history. Among them we could mention the poet Dahyeong Kim Hyeon-seung, or the painter Bae Dong-shin, as well as Jeong Jun-chae, Jeong Chu’s older brother. However, the people of Gwangju are not really familiar with them. I firmly believe that in order for Gwangju to further strengthen its identity as a cultural and artistic city, as well as to strengthen its citizens’ sense of identity, more and deeper research on these important people should be done. For example, in France, the place where the famous painter Monet used to dwell has been developed into a tourist destination and has become a place that many people visit. So, it is my opinion that we as Gwangju citizens ourselves should first and foremost recognize the values of these amazing Gwangju people who all have made a great mark in recent Korean history. Only then will we be able to compare to cultural and artistic cities in other countries.

Interviewer’s Note: During his lifetime, Jeong Chu longed for the reunification of Korea and hoped that his song “My Homeland” would become the national anthem of his country. Unfortunately, he passed away in Almaty, Kazakhstan, at the age of 90 on June 13, 2013, without being able to witness either.

The Interviewer

Jeong Jiyeon studied piano at university in Seoul and has now returned to her hometown of Gwangju where she works as a coordinator at the Gwangju International Center.

*This article was originally published in Gwangju News December 2020 issue.

Gwangju News is the first public English monthly magazine in Korea, first published in 2001 by Gwangju International Center. Each monthly issue covers local and regional issues, with a focus on the stories and activities of the international residents and communities. Read our magazine online at: www.gwangjunewsgic.com

*이 글은 광주뉴스 2020년 12월호에 실린 내용입니다.

광주뉴스는 광주국제교류센터가 2001년에 처음 발행한 대한민국 최초의 영문 대중월간지입니다. 매월 발행되는 각 호에는 지역에 거주하는 외국인과 지역민의 활동과 지역사회의 이야기 및 이슈를 다루고 있습니다. 온라인에서도 잡지를 볼 수 있습니다. (www.gwangjunewsgic.com)

원문 해석

③고려의 노래

Gwangju News December Issue

본 글은 광주가 낳은 음악가이자, 또 광주에서 잊혀진 음악가이자, 격동의 한국근현대사에 휘말린 한 이민자의 인생을 재조명하고자 기획되었으며, 정헌기 문화기획자와의 인터뷰를 바탕으로 대담형식으로 재구성되었습니다.

광주뉴스 11월 호 <②검은 머리 차이코프스키>에서 이어집니다.

러시아(당시 소련)의 모스크바 음악원에서 유학중이던 정추 선생은 김일성 우상화 반대운동을 도모했다는 이유로 북한 당국으로부터 체포 명령을 받게 된다. 이에 선생은 흐루시초프 서기장에게 직접 편지를 써 망명을 신청했고, 북한으로의 강제송환은 면한 대신 카자흐스탄의 알마티로 추방됐다. 소련에서 정추는 추방된지 17년이 지난 1975년에야 시민권을 받을 수 있었다.

러시아에서 김일성 우상화 반대운동을 일으킨 것을 이유로 카자흐스탄 알마티로 추방되셨다고 했습니다. 이후 카자흐스탄에서의 삶은 어떠셨는지, 어떤 일들을 하셨는지 듣고싶습니다.

1958년에 카자흐스탄에 가서는 고려인 사회를 마주치게 됩니다. 그런데 아시다시피 중앙아시아에 있던 고려인들에 대한 스탈린의 만행들 때문에 정추 선생님이 굉장한 충격을 받으셨어요. 심지어 선생님 작품중에 ‘1937년 9월 11일 스탈린’ 이라는 중앙아시아의 고려인 강제이주 사건을 담은 교향곡도 있을 정도입니다. 또 하나 기억할만한 업적이라하면 고려인들의 구전가요를 채록하셨던 것을 들 수 있는데요. 당시 출시됐던 휴대용 녹음기를 가지고서 시베리아 횡단열차 안에서 고려인들을 찾아다니면서 녹음하시고, 또 그걸 악보화하는 작업을 하셨습니다. 그렇게 수집하신 구전가요가 1천 곡이 넘습니다. 이렇듯 민속음악 연구에 몰두하실 수 있었던 건, 음악가였기도 했지만, 망명자 신세였던 선생께서 고려인들이 겪는 이방인으로서의 설움과 비애를 남다르게 받아들이셨기 때문이었을 거라고 생각해요.

카자흐스탄으로의 망명 초기에 정추의 대표적인 오케스트라 음악이 모두 탄생했다. 이후 1970년대 말부터 1990년까지는 주로 민속음악학자로서의 연구활동과 대학교수로서의 교육활동에 매진하였다. 특히 카자흐스탄의 음악 교과서에 그의 작품 60여 곡이 실렸고, 1988년 카자흐스탄 정부로부터 ‘공화국 공훈 문화일꾼’ 칭호를 받았다.

정추 선생님의 후손으로서 선생님이 어떤 음악가로 기억되기를 바라시는지 의견을 듣고 싶습니다.

사람들이 정추 선생에 대해 다소 이벤트적으로 접근하려는 경향이 있는 것 같아요. 그 분의 생애와 업적을 발굴했을 때 이게 사회적으로, 경제적으로, 그리고 정치적으로 어떻게 영향을 미칠 것인가를 생각하는 거죠. 하지만 당시의 시대적 상황을 되새기면서 이 사람이 일제강점기에 태어난 한국인으로서, 이념대립이 첨예하게 일어났던 전후(前後) 음악가로서 어떤 인생을 살아왔는 가에 더욱 재조명이 되었으면 좋겠다는 바람이 있습니다.

그리고 정추 선생 뿐만 아니라 근현대사 속 광주 출신 인물들 중 굉장한 분들이 많아요. 다형 김현승 시인 이라던가 배동신 화백이라던가, 그리고 정추의 형이었던 정준채 선생이라던가. 그런데 광주사람들이 잘 모르죠. 저는 우리 광주가 예향이라는 도시 정체성을 더욱 확고히 하고 시민들의 자의식을 강하게 하기 위해서는 이런 인물들에 대한 발굴과 연구가 더욱 이루어져야한다고 생각해요. 예를 들어 프랑스의 경우, 모네가 머물렀던 곳 자체가 관광지로 개발되고 많은 사람들이 오가는 곳이 된 것처럼요. 우리 도 한국 근현대사에 큰 획을 그었던 광주 출신 인물들에 대해 우리 스스로가 가치를 정립해야만 하고, 바로 거기로부터 다른 나라의 도시들과 경쟁력이 생긴다고 봅니다.

정추 선생은 생전에 통일을 염원하며 만든 ‘내 조국’이란 곡이 조국의 애국가가 되길 바랬다. 그러나 ‘내 조국’이 애국가가 되는 것도, 조국의 통일도 두 눈으로 보지 못한 채 2013년 6월 13일에 90세라는 나이로 카자흐스탄 알마티에서 타계하였다.

인터뷰& 번역

정지연은 대학에서 음악을 공부한 뒤 고향인 광주로 돌아와 광주국제교류센터에서 간사로 일하고 있다. 여가시간에는 드라마와 영화를 보며 시간을 보낸다.